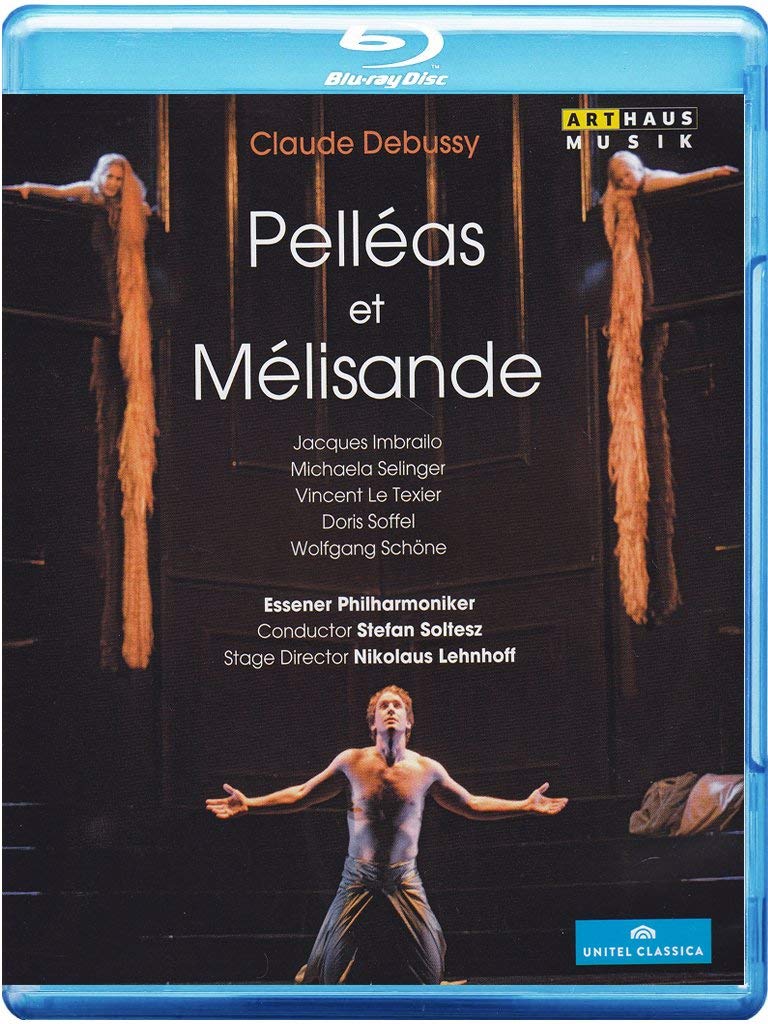

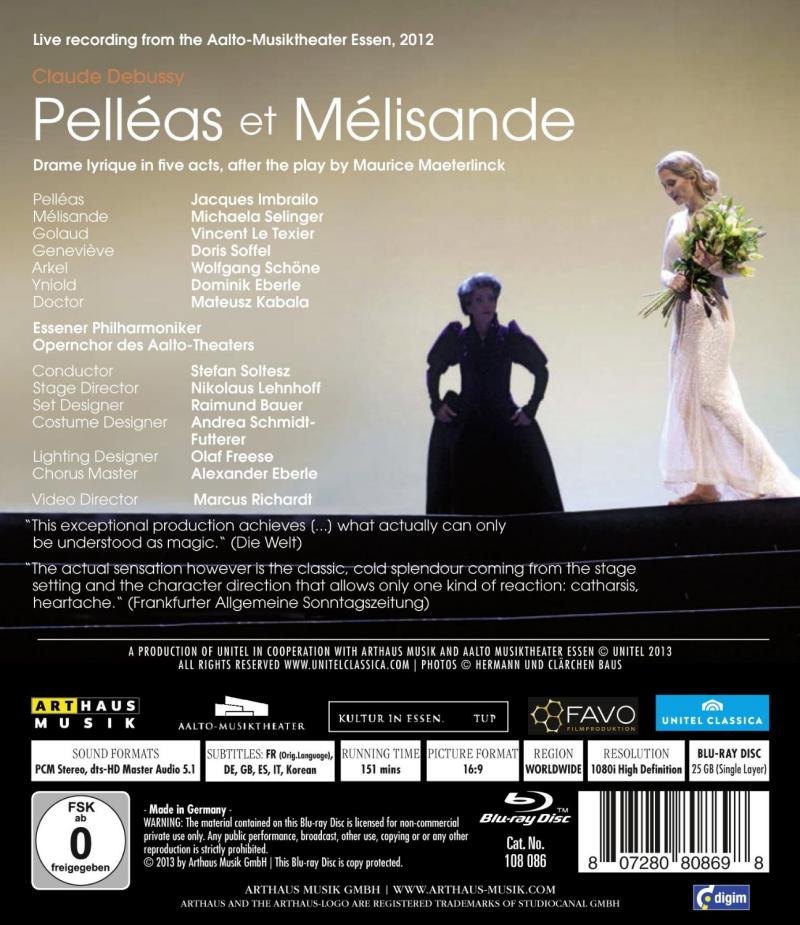

Debussy Pelléas et Mélisande opera to libretto by Maurice Maeterlinck. Directed 2012 by Nikolaus Lehnhoff at the Aalto-Musiktheater Essen. Stars Jacques Imbrailo (Pelléas), Michaela Selinger (Mélisande), Vincent Le Texier (Golaud), Doris Soffel (Geneviève), Wolfgang Schöne (Arkel), Dominik Eberle (Yinoid), and Mateusz Kabala (Doctor). Stefan Soltesz conducts the Essener Philharmoniker and the Opernchor des Aalto-Theaters (Chorus Master Alexander Eberle). Sets by Raimund Bauer; costumes by Andrea Schmidt-Futterer; lighting by Olaf Freese. Directed for video by Marcus Richardt. Sung in French. Released 2013, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A

Pelléas et Mélisande is a made-up-from-scratch Medieval-age fairy tale first presented in 1893 as a play by the symbolist author Maurice Maeterlinck. Symbolism was an art movement represented by writers like Poe, Baudelaire, and Mallarmé as well as plastic artists like Böcklin, Schwabe, Klimt, Redon, and Munch. As described by Jean Moréas, in symbolism things that happen in the world ". . . will not be described for their own sake . . . they are perceptible surfaces created to represent their esoteric affinities with the primordial Ideals." This statement also describes Debussy’s stated aim that music not be limited to a “more or less exact representation of nature but rather to the mysterious affinity between nature and the imagination.” So Pelléas et Mélisande became the perfect vehicle for Debussy's landmark modern opera first staged in 1902.

Symbolist works are inherently open to interpretation in various styles. For example, here’s Pelléas and Mélisande depicted by Carlos Schwab in 1923:

And in contrast, here’s a recent Robert Wilson design!

We now have (early 2020) four Blu-rays of Pelléas et Mélisande in strikingly different styles. But the Lehnhoff version is a landmark recording which likely will be be considered for a long time a classic Pelléas et Mélisande for the 21st century. Lehnhoff’s mise-en-scène uses abstract modern sets, archaic designs, moody lighting, and creative photography to evoke a mysterious and hallucinatory atmosphere in and around the dark castle of King Arkel. The name of the castle is Allemonde (an invented word meaning “all the world”).

The visual images created by Lehnhoff and TV director Marcus Richardt mesh seamlessly with Debussy’s ethereal music. Lehnhoff’s monumental castle is populated by 6 members of Arkel’s family, all so ill-defined in their personalities as to be called symbols rather than characters. But Lehnhoff’s wrings out of his singers a degree of acting ability one usually associates with theater or movies rather than opera.

Before we get into screenshots, a word about picture quality is needed. This is the only opera I know of that appears to have been recorded, for valid artistic reasons, with a scrim in front of the stage throughout and in mostly low light. 2012 is also fairly early in the era of HD video (which began 2008). Videographer Richardt, a German film director, was doubtless concerned whether he could get satisfactory picture resolution under these circumstances. But he was told to shoot for mood rather than high-resolution accuracy. As Lehnhoff says in his excellent article in the the keepcase booklet, ”Allemonde is both a mortuary and a prison, a cave and a burial chamber, a symbol of the interior of the soul. All life inside these walls is dead . . . the characters are at the mercy of their subconscious . . . .” Pin sharp resolution was not the goal when this recording was made in HD. (I rather imagine this recording would be unwatchable in DVD.)

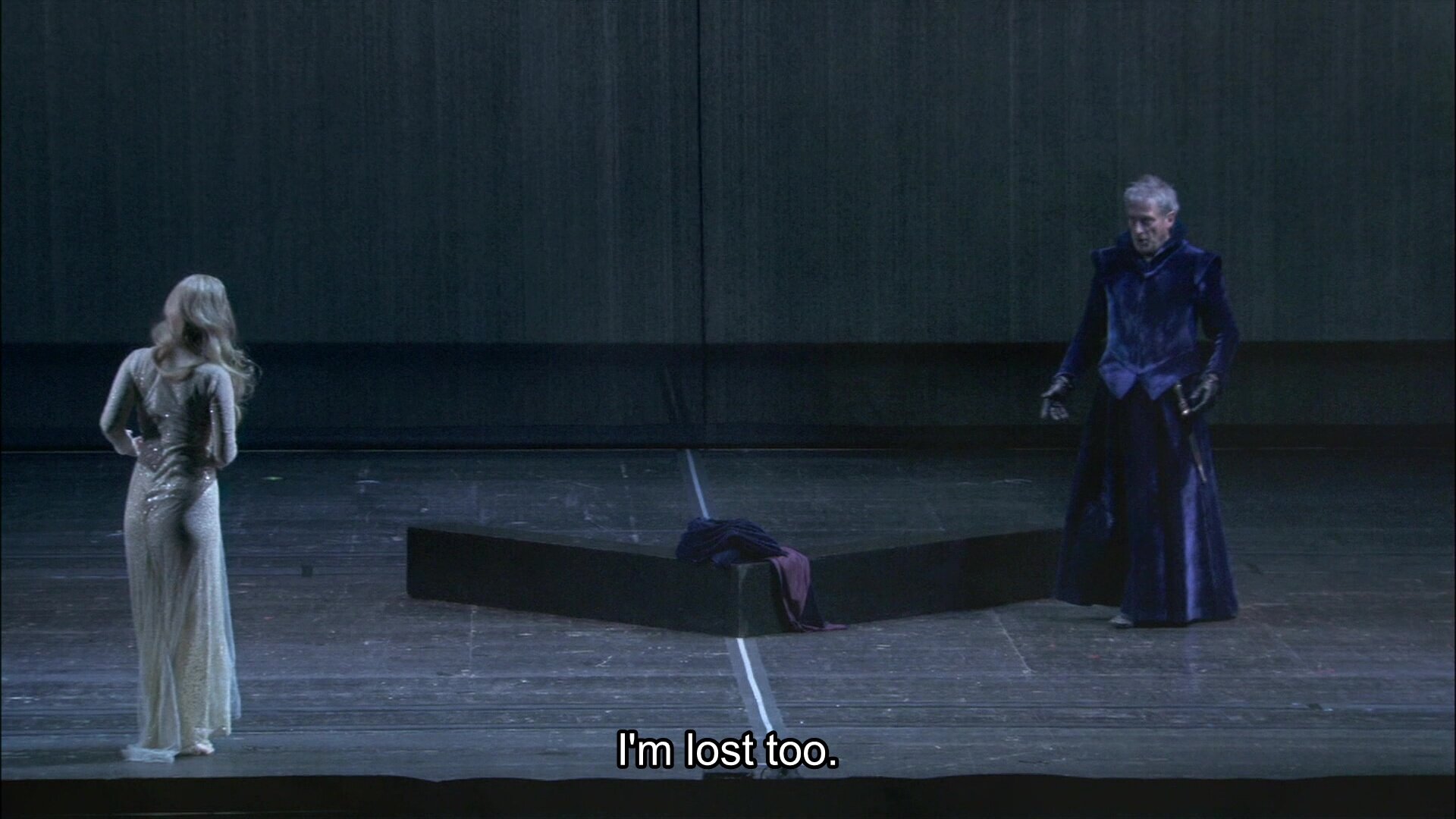

In our first screenshot we see the beautiful, young, mysterious Mélisande (Michaela Selinger) being discovered by Prince Golaud (Vincent Le Texier) at a spring deep in a forest. She has escaped from some terrible danger and is lost. Selinger is a fine singer and perhaps an even better actress. She is the right age for this role and able to convince you that a man might murder another man — even one he loves — to protect his right to possess her:

Prince Golaud is a lonely widower who is traveling in foreign lands to forget this troubles. His grandfather is King Arkel of Allemonde (Wolfgang Schöne). Prince Golaud is immediately smitten by Mélisande and convinces her to accept his protection. Although he will never learn who she is, where she is from, or what terrible things happened to her, he will soon marry her as he continues his travels. (Debussy was forever trying to distinguish himself from Wagner. Here we have a married couple with an inscrutable, unknowable victim as wife, the flipside of Wagner’s inscrutable, unknowable hero-husband named Lowengrin.) Already in the screenshots above and below we see Lehnhoff’s mastery of blocking and personal directing in bringing the story to life aided only by a simple set, conservative costumes, and minimal props. The words of the characters, taken directly from the stage play, tend to be loaded with irony and other secondary meanings:

Next we meet the rest of the adults in the family: King Arkel, Geneviève (Doris Soffel), and Pelléas (Jacques Imbrailo). Although the family is small, there is an intricate backstory for them that was dreamed up by the playwright Maurice Maeterlinck. The libretto gives enough hints about the family history, but on first viewing you likely will remain confused about who is who. (Even the experts have trouble with this.) So I worked up a detailed genealogy for you. For now, you should know that Geneviève is the King’s daughter-in-law, that Geneviève is the mother of Prince Golaud and Pelléas from two different marriages, and that Pelléas and Prince Golaud are half-brothers. Pelléas is much younger than Golaud and has never been married. In the screenshot below, Pelléas asks for permission to visit a sick friend. But Arkel instructs Pelléas not to leave Allemonde because Pelléas’s father is also ill, confined to his quarters in the castle, and in need of support from Pelléas:

So Pelléas is stuck at home when Prince Golaud and Mélisande arrive as newly-weds. In our next screenshot, Pelléas greets his new sister-in-law. It’s love at first sight for both, and this brief moment is to be the greatest happiness that either of them will ever know. It’s not too surprising to see this double image from Marcus Richardt, a film director who is used to this sort of thing. I usually don’t much care for trick photography, but the image below does reinforce the significance of this moment for us in the HT. It must be hard to get across to members of a live audience the importance of this first meeting for Pelléas and Mélisande:

None of the Arkel family will ever know who Melisande was, but we do. She is a water spirit (sprite?) and sister of Ondine, the Rheinmaidens, Rusalka, and the Little Mermaid. That’s why Prince Golaud found her at a spring and why so many other important scenes in this story take place at water features such as a spring, a fountain, a septic tank, or a grotto. She is the symbol of the eternally unattainable beauty and purity of the female (no mermaids for mermen) who brings disaster down on him who lusts after her. In the screenshot below, Pelléas shows Mélisande an old fountain near the castle. It’s called the Fountain of the Blind because those who drink from it are helped to see again. Unfortunately, all the members Arkel’s family other than Pelléas have abandoned the fountain to the forest and no longer seek aid from its waters:

Below a closer look at Prince Golaud — too old for an Ondine:

Mélisande loses her wedding ring (probably the ring Prince Golaud also gave to his first and deceased wife) when she is visiting the Fountain of the Blind. Enraged at what is happening around him, Golaud sends Mélisande and Pelléas out at night to look for the ring:

Lehnhoff and Richardt make masterful use of near shots and close ups throughout the video file. In the shot below even Mélisande’s hair flows like a liquid:

Although Pelléas et Mélisande has a simple plot, it is not easy to produce because it has numerous scenes that suggest fantastic sets: a mysterious spring in forest stocked with game to hunt, an ancient fortress castle with a forbidding interior and a massive door with heavy chains, a wild garden overlooking a mountainous coastline with a port for sailing ships, lighthouses for signalling to ships, the mysterious Fountain of the Blind, a beautiful grotto on the shore carved out of the rocks by the ocean waves leaving beautiful seashells behind, a beach for swimming, a tower with a balcony from which Mélisande can let down her hair that is longer than she is tall, a dangerous dungeon under the castle filled with foul odors from centuries of occupation of the castle by the royal family and their followers, and the bodies of peasants, dead and alive, laid low by a famine stalking the kingdom. The most challenging scene to stage would be Mélisande letting down her hair from the tower window. For their tower scene, Lehnhoff and Richardt appear to have use several different tricks including special wigs, a dummy double for Mélisande, and projection of hair images on the scrim. Or maybe some of what we see below was done in post-production and looked quite different to the live audience. In any event, the comment of Pelléas in the subtitle is apt:

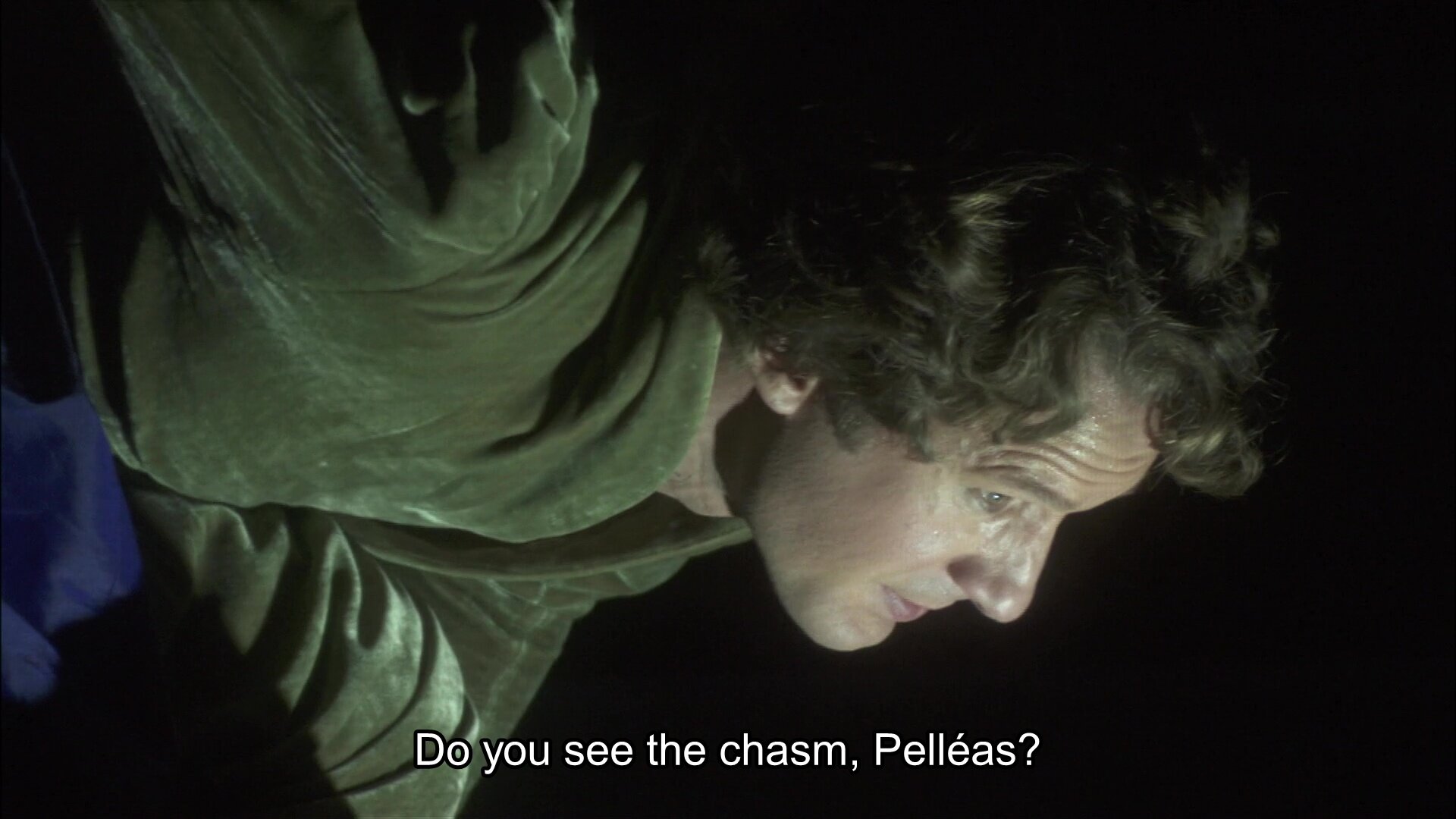

Prince Golaud forces Pelléas to visit the vaults under the castle where the sewage from the kingdom decays (more water, this time dirty):

Pelléas emerges from his visit to the vaults happy that Golaud didn’t push him into the chasm:

Prince Golaud has a young son, Yniold (Dominik Eberle ) who has grown close to his step-mother Mélisande. Golaud uses Yniold to spy on “mummy” and uncle Pelléas, who now spend most of their time together. Golaud is sure Mélisande is unfaithful. But in a beautiful close-up, Yniold defends them saying that they are good and:

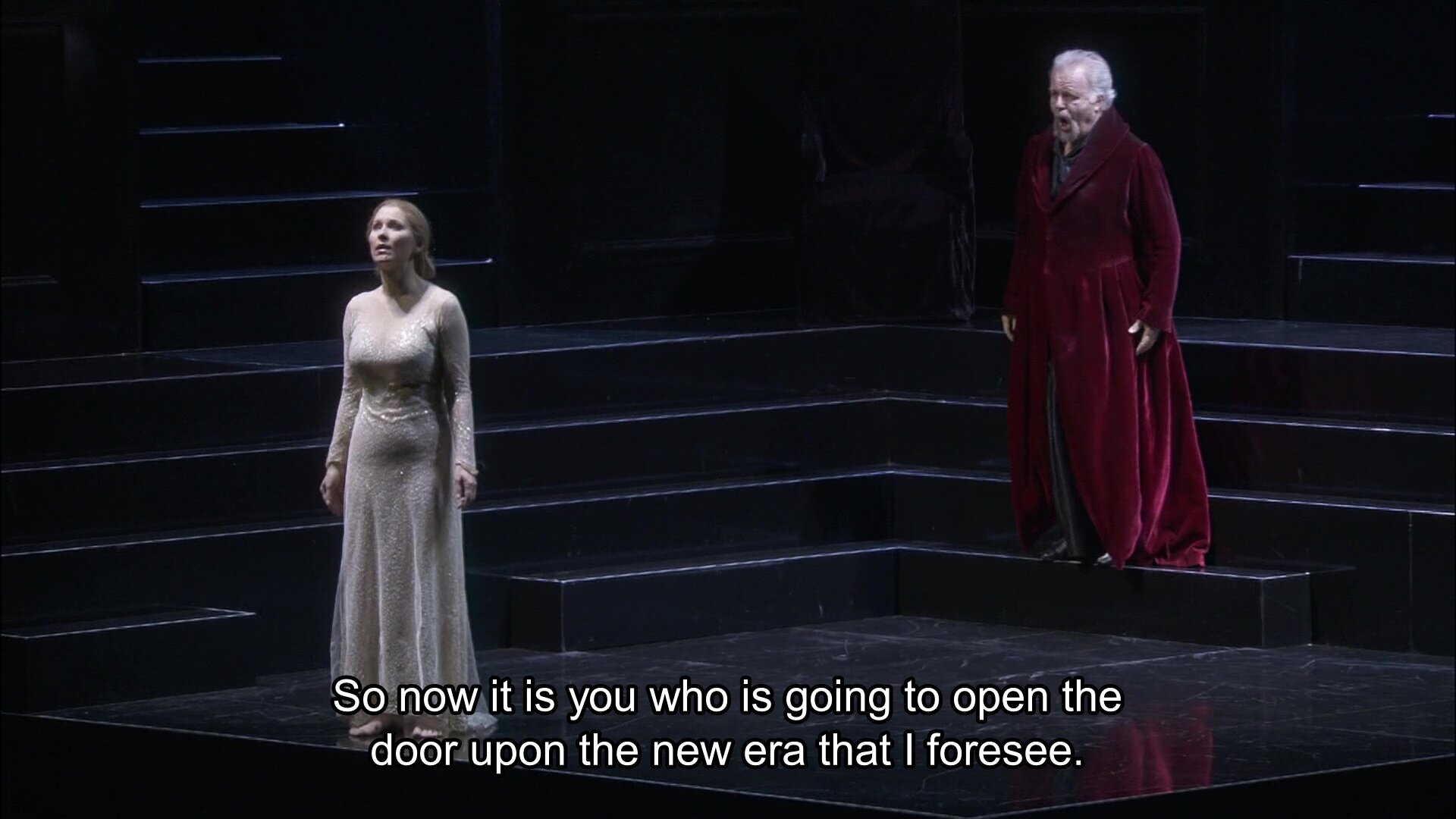

King Arkel is oblivious to the tension between Prince Golaud and his wife and half-brother. But Arkel knows something is wrong. When the father of Pelléas suddenly recovers from his long illness, Arkel believes a curse on the castle has been lifted. He hopes Mélisande’s youth and beauty will inspire new happiness in the family. This is, of course, just more dramatic irony to further baffle poor Mélisande and screw even tighter the tension surrounding her:

But Arkel’s hopes are dashed when he sees Prince Golaud, now mad with frustration and rage, threaten his wife with his sword even though Golaud knows she is pregnant:

Prince Golaud calls on the spirit of Absalom. In case you have forgotten the Bible story, I’ll remind you that Absalom was a King of Israel who killed his half-brother in revenge for the rape by the half-brother of Absalom’s full sister. Pelléas is doomed:

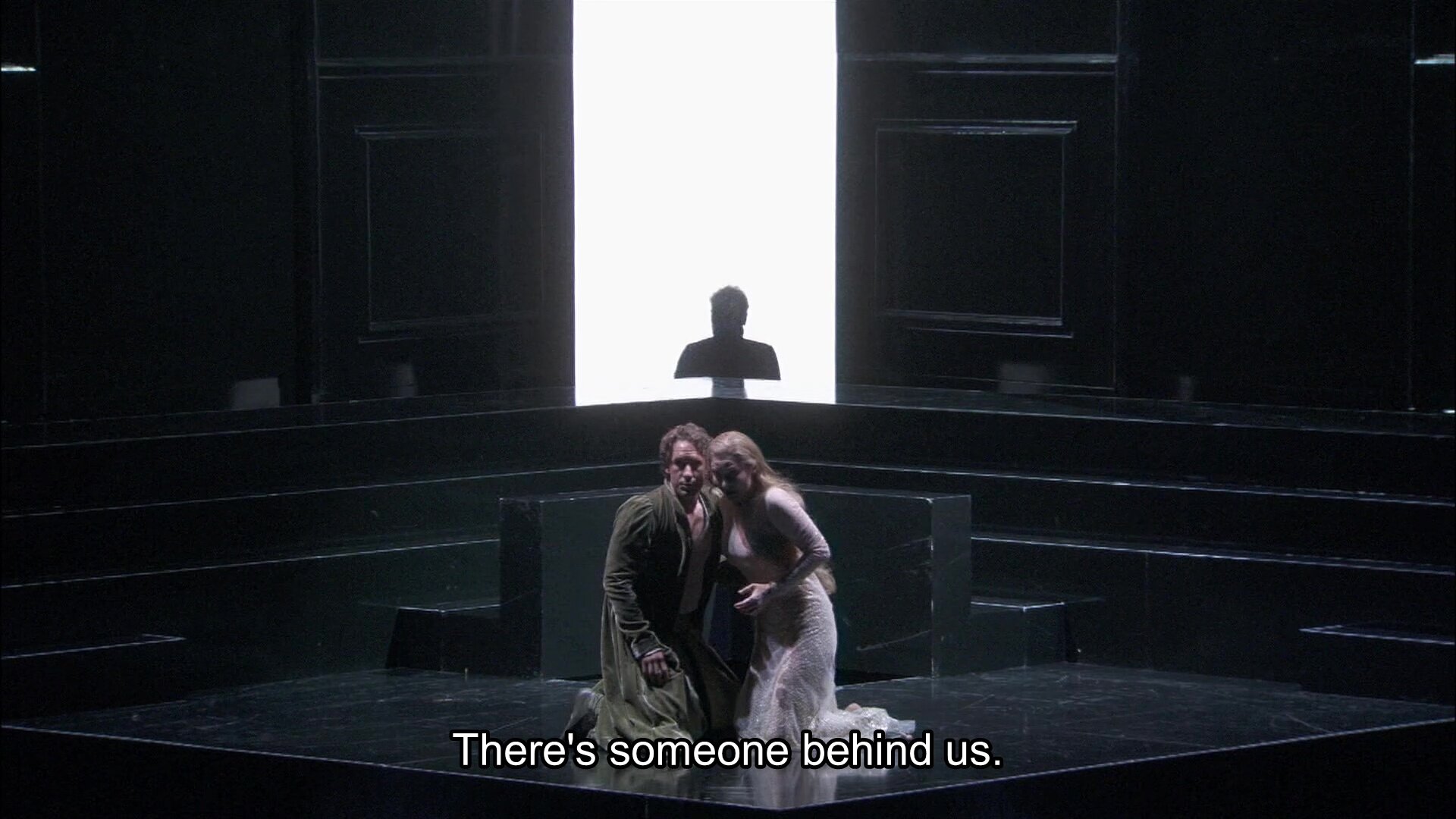

Arkel gives Pelléas permission to leave the kingdom. He meets with Mélisande one last time to finally declare, in parting, his love for her:

It’s not too hard to guess how this will end, but if you don’t already know, I’ll not completely spoil it for you.

A few words about the music. According to Steve Reich (“A Brief History of Music”, bonus extra to Phase to Face) Wagner’s music pointed toward the abandonment of harmony toward new atonal music. This was the “German path” followed most famously — into oblivion — by the Second Viennese School of composers like Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. But Reich credits Debussy with saving harmony by inventing a “French path” of more liberal and fluid harmonic modes used later by 20th century opera composers such as Poulenc, Britten, Barber, Korngold, and even the serialists such as Reich and Philip Glass.

Although Debussy continued to use a harmony of this own invention, in Pelléas et Mélisande he also broke with opera tradition by elevating his text to a level of importance then new to opera. At the first rehearsal, Debussy personally told his cast, “First of all, ladies and gentlemen, you must forget that you are singers.” He meant by that that the libretto did not have poetic language constructed and rhymed to support soaring melodies for showcase arias and enticing combinations of voices in duets, trios, and the like. There would be no spoken parts, and every word was sung, but in a manner that would support the overall atmosphere of the piece rather than give singers opportunity to show off their fancy skills. Debussy himself wrote an article saying he wanted his characters to “sing like real people.”

And Debussy, who was already famous as a brilliant composer for the orchestra, also took a backseat to the text. As explained by George Martin in The Opera Companion page 635 (new edition, 2008), “Because the music accompanies conversation rather than bursting into song, its sound is subtle and minutely varied. It is like a surface of water, nothing in and of itself, yet infinitely varied in color and texture as the light and air change above it.” I should warn you that you never see the Essener Philhamoniker in this video. The orchestra interludes are played, but during them Lehnhoff puts up signboards explaining what you are going to see in the next scene. These signboards help the director a lot in convincing you that, for example, what you see next is in fact an abandoned fountain in an overgrown garden.

Pelléas et Mélisande is also considered a turning point in the history of opera also because the libretto was taken literally from written literature (with necessary cuts and simplification) rather than being written up as poetry by a librettist. Almost every word comes straight from the Maeterlinck’s theater play (with cuts for economy and clarity). Other works that followed this approach later would be, for example, the Richard Strauss Salome (1905 ) and the Berg Wozzeck (1925). Pelléas et Mélisande and Wozzeck are also similar in that they both consist of a mosaic of individual scenes rather than a linear story line. Lehnhoff helps out his audience with detailed textual introductions to each of his scenes. These introductions are very helpful to the newcomer. If you already know the opera, these signboards may get wearisome, but there’s nothing you can do avoid them.

Finally, I’ll suggest — just for fun — that in the future Debussy may be remembered as the first composer to write a motion picture soundtrack (without realizing what he was doing). The motion picture industry got going in 1892, and in 1895 you could see longer silent films in Paris venues. True, sound would not come along until the late 1920s. But Debussy must have known about the impact that electric technology was having during his time on all aspects of life.

Could Debussy have understood, perhaps unconsciously, that the operas and singspiels of the past would become the motion pictures of the future? The movies have for sure wiped out opera as the popular mode of hear-see entertainment. And there have only been a few decent movies made so far of operas. Finally, the movie industry has produced little or no music of opera quality because movie soundtracks must be composed to order in the time frame of months rather than years. (Debussy worked on Pelléas et Mélisande for two years before it opened and he continued to improve the score for 8 years after that.)

But could it be that the golden age of movie operas still lies in the future? There were 17 live productions of Pelléas et Mélisande in the 2018-2019 opera season. That’s more than a drop in the bucket, but it remains that the chances are nil for most of the people on earth to see Pelléas et Mélisande live. So maybe that’s why Lehnhoff and Richardt made this video as close as they could to a movie (while working with a live stage production that had already been paid for). Could subject title be properly considered a made-for-TV movie? Could Richardt one day get the financial backing to make a real movie of Pelléas et Mélisande on location at a dark castle overlooking an ocean? Just last month, François Girard, another artist who directs movies and opera, wrote (March 2020 Opera News at page 33) that opera is the “mother of film.” Could it be the child of opera is still growing up?

Now to a grade. I’ll knock A+ down to A- for the weakness in resolution discussed. But once I creep into the dark pile of castle Allemonde, the dramatic impact of the directing, singing, and orchestration is strong enough to bring me back up to A. But I’ll warn you. This in not an easy A : this one makes you to work some.

OR