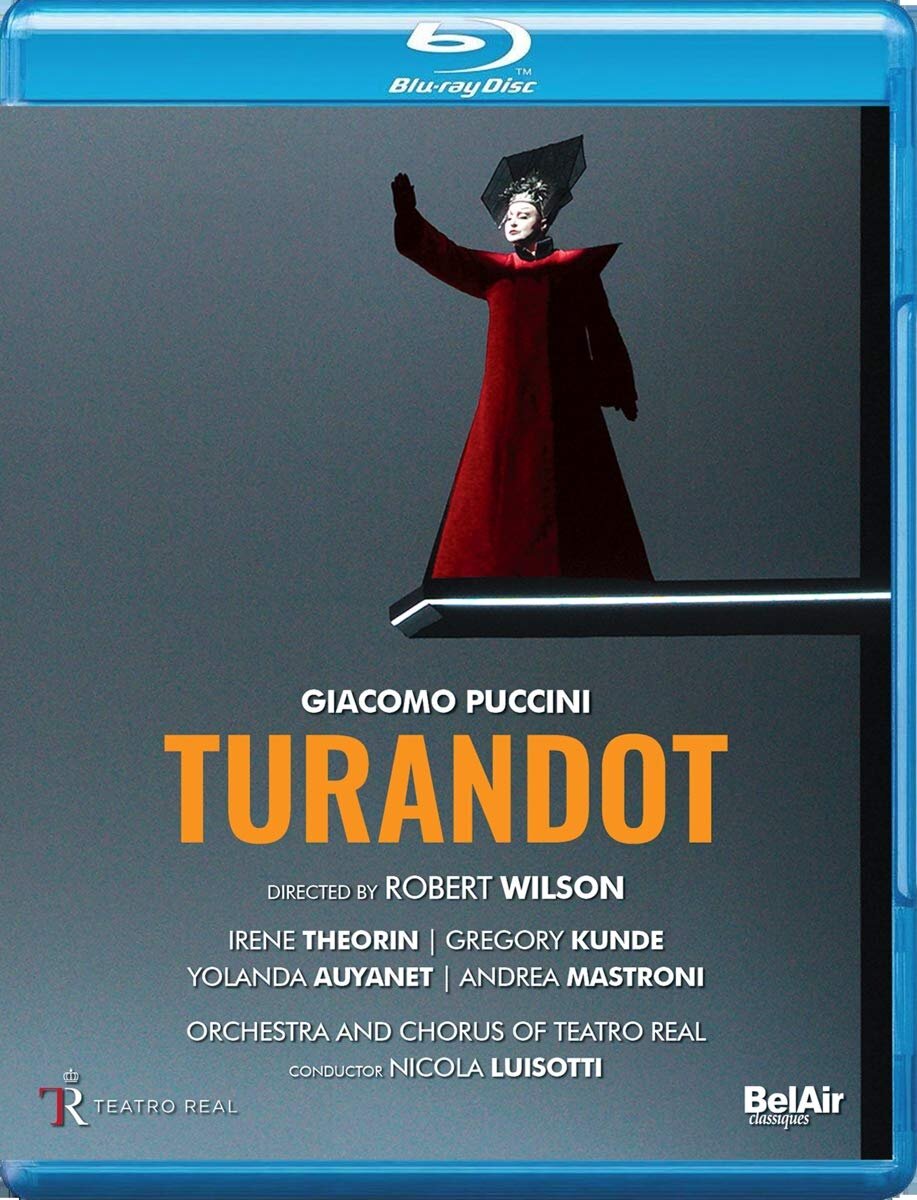

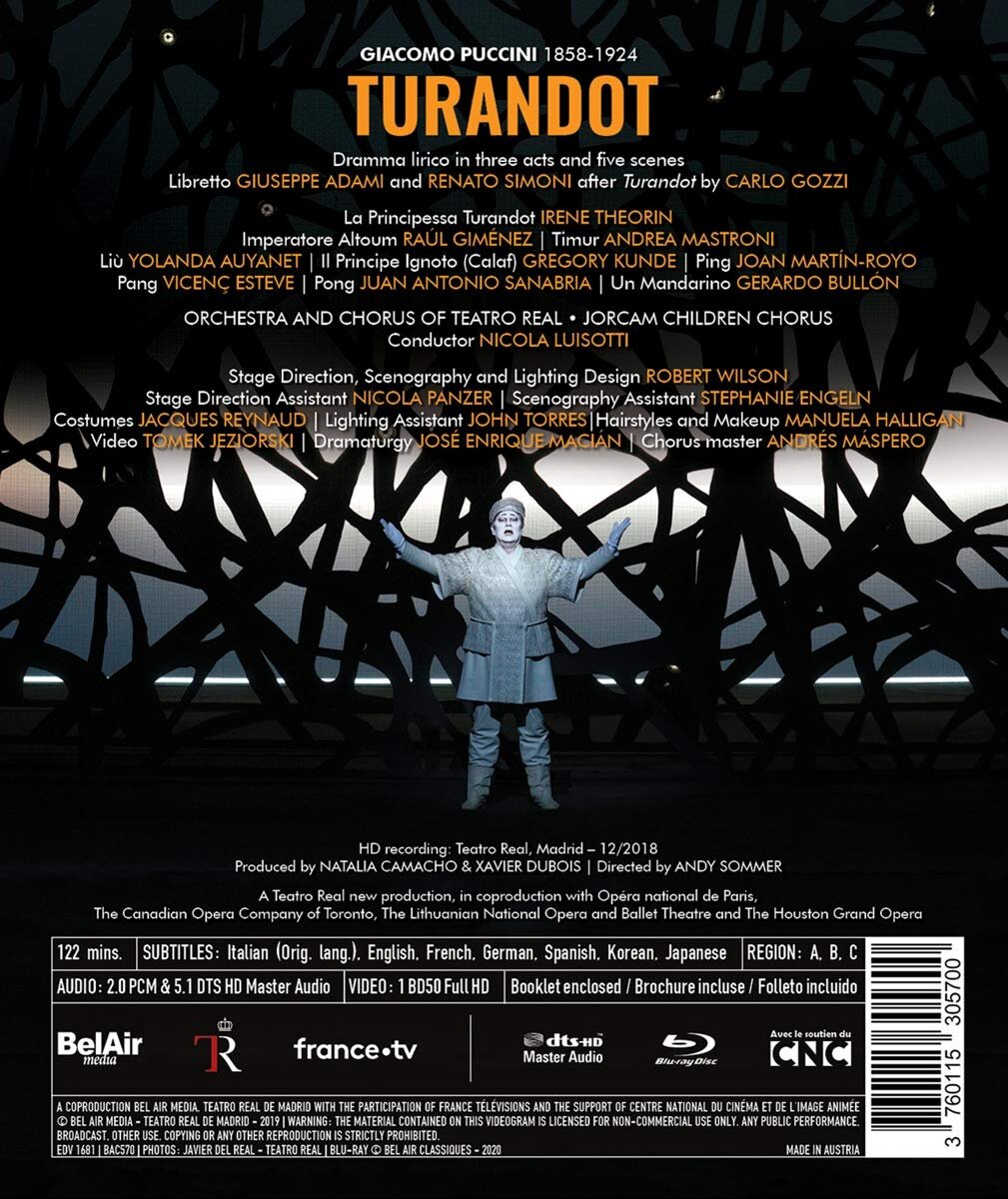

Puccini Turandot opera to a libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simon. In 2018 Robert Wilson directed (with assistant Nicola Panzer), designed the sets (with assistant Stephanie Engeln), and designed the lighting (with assistant John Torres) for Turandot at the Teatro Real in Madrid. Stars Irene Theorin (Turandot), Raúl Giménez (Imperatore Altoum), Andrea Mastroni (Timur), Yolanda Auyanet (Liù), Gregory Kunde (Il Principe Ignoto [Calaf]), Joan Martín-Royo (Ping), Vicenç Esteve (Pang), Juan Antonio Sababria (Pong), and Gerardo Bullón (Un Mandarino). Nicola Luisotti conducts the Orchestra and Chorus of Teatro Real and the Jorcam Children Chorus (Chorus Master Andrés Máspero). Costume design by Jacques Reynaud; hairstyle and makeup by Manuela Halligan; video design by Tomek Jeziorski; dramaturgy by José Enrique Macián. Directed for TV by Andy Sommer; produced by Natalia Camacho and Xavier Dubois. Sung in Italian. Released 2020, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio surround sound. Grade: A

Turandot as Blank Canvass

It’s 2020, and we now have splendid HDVDs of hundreds of operas. We also have multiple discs of many warhorses such as 12 versions of Don Giovanni (Mozart), 12 La traviatas (Verdi), and 8 of Parsifal (Wagner). Of all these multiple versions, the one opera that seems to inspire the most astonishing variety of directorial concepts might be Puccini’s last work, Turandot, of which we now have 10 versions.

For the traditionalist, we have the Zeffirelli super-kitsch show at the Met featured in the next two screenshots of (1) Turandot and (2) the Emperor:

Contrast Zeffirelli to the slick concepts of Stefano Poda inspired by modern luxury marketing. In the next screen shot below, Turandot is the big girl in the middle of a platoon of lookalikes:

And here the Emperor (the gent in focus) is on foot instead of sitting on a throne:

And now compare all of the above to the surreal dreamscape of Robert Wilson and consider if this is good evidence that Turandot is the closest thing in opera to a blank canvass for the director and designer:

Robert Wilson

Wilson is my favorite opera director because we are neighbors. I live in Dallas, Texas, a cowboy town that somehow became today one of the top 10 major economic centers in the world. But when Wilson was born in 1941, he arrived in Waco, TX about 100 miles south of Dallas. Waco is most famous for the “Waco siege” in 1993 when the US Government burned down the Branch Davidian cult compound killing 51 adults and 25 children. But that was long ago. Today the reputation of Waco has recovered, and it is the proud home of the Texas Rangers Museum and the Doctor Pepper Museum. In Wilson’s youth, the most exciting thing to do in Waco was to sit in a blind hoping a deer would come by. Artistically inclined and interested in the theater, life for Wilson in Waco must have been atrociously suffocating.

After several years studying business administration at the University of Texas (no doubt to please his parents) Wilson made his escape to New York. Although most famous for his opera productions, his range as graphic artist is universal and gloriously varied. His most famous project was as “writer” and designer of Einstein on the Beach in 1976. That was also long ago. Today Wilson is close to age 80, but he appears to be about as active worldwide as ever. In 2020 we have, in addition to subject title, five opera HDVDs directed by Wilson: Adam’s Passion, Einstein on the Beach, Der Messias, L’Orfeo, and Le trouvère.

Everything Wilson presents on stage is the exact vision he has in his mind’s eye of the subject. And since he hasn’t changed his mind about things during his career, his stage work is instantly and unmistakably recognizable.

In Wilson’s shows, there is usually no attempt to suggest any real place or any particular time. Wilson’s default color seems to be gray-blue against black. Many actions transpire in slow-motion. The sets are abstract and symbolic. Videographers tend to shoot his works full-stage and straight on from the center of the house with only occasional near shots or close-ups (probably Wilson encourages this). Wilson loves to use LED-style lighting strips to frame his visions. All of these elements are illustrated in the screenshot below of the Prince of Persia, who couldn’t solve Turandot’s riddles and is on his way to torture and death. But Wilson doesn’t allow his images to become boring. No matter how static a scene may be, there will be Wilson accents or twists. Below one accent is the Prince’s ornate crown that contrasts with his naked torso. The executioners are made up with fearsome black bars dividing their faces. They carry extremely long, sharp, and dangerous-looking spears. When they march, the twist is that they unexpectedly execute precisely simultaneous rotations of their bodies as steps. All this underscores the implacability of the doom falling on the Prince:

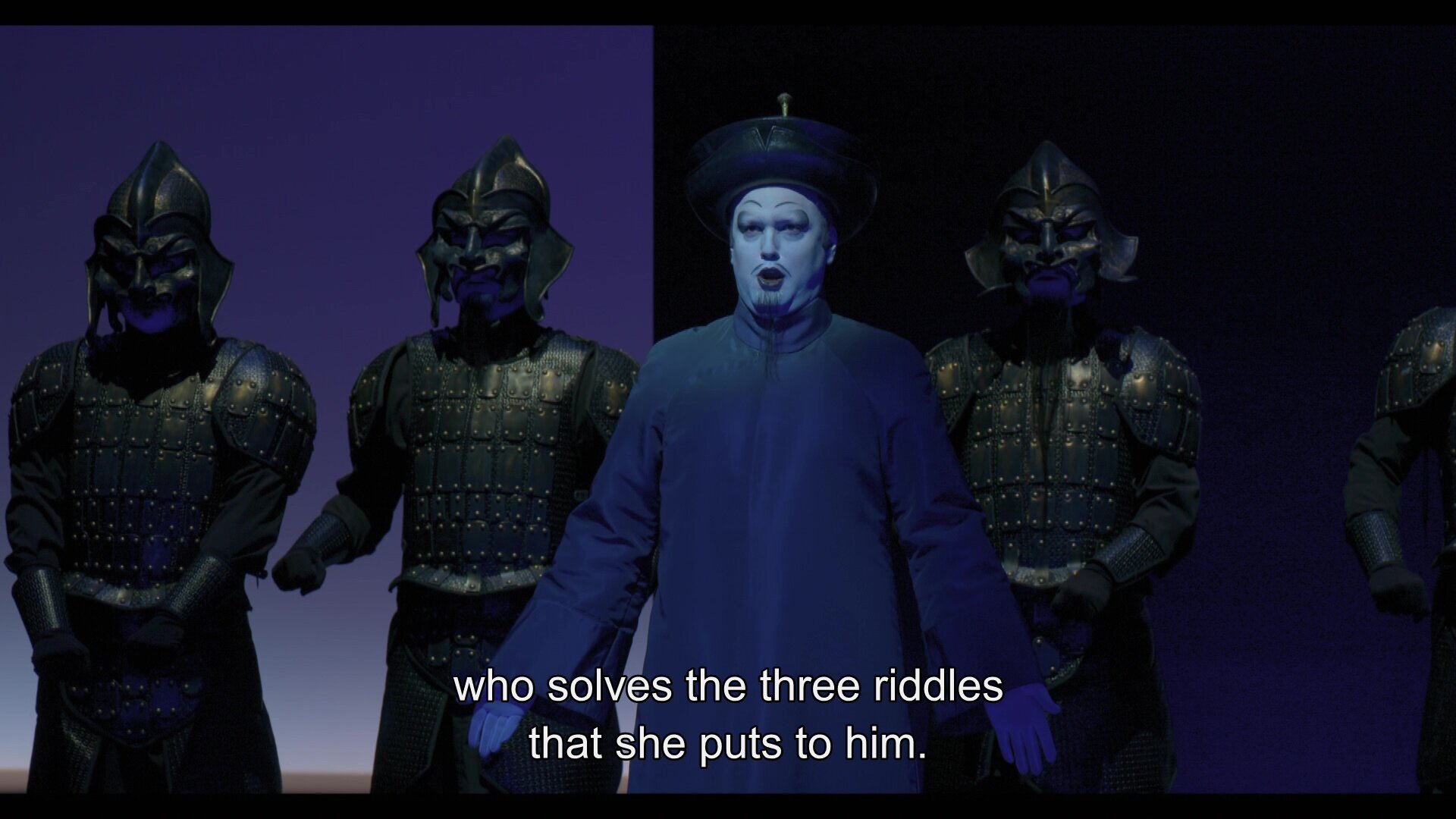

Wilson has his own unisex makeup style which you can see in the image below of the Manderine (Gerardo Bullón) nnouncing Turandot’s Law of the Riddles. The face is slathered in flat white. The eyes are surrounded by large shadows, artificial hair is painted on, and the lips are accentuated in purple or bright red. But here the Wilson twist is his costumes for the guards—ancient armor giving them a fierce and rather authentic look:

Next below is a shot made from off-center. Now the framing light strip appears not to be horizontal, which may make the image look off-balance. Here we see from right to left Calaf (Gregory Kunde ), Timur (Andrea Mastroni ), and Liù (Yolanda Auyanet):

Next below is a close-up of Liù. The twist would be her elaborate jewelry. This might seems inconsistent with her status as a slave taking care of a ruined master. But Wilson’s reference here would be her sterling character, not her net worth:

Wilson prefers to use a real prop to video, and he likes to work in some kind of animal. Ergo, below is his big bird with flapping wings all controlled by wires from the fly. The chorus has a big part in Turandot, and all the singers are made up in white-face. There are no dancers in this production, but the chorus must learn many moves that must be performed simultaneously—this probably required a lot of rehearsals with assistant stage director Nicola Panzer:

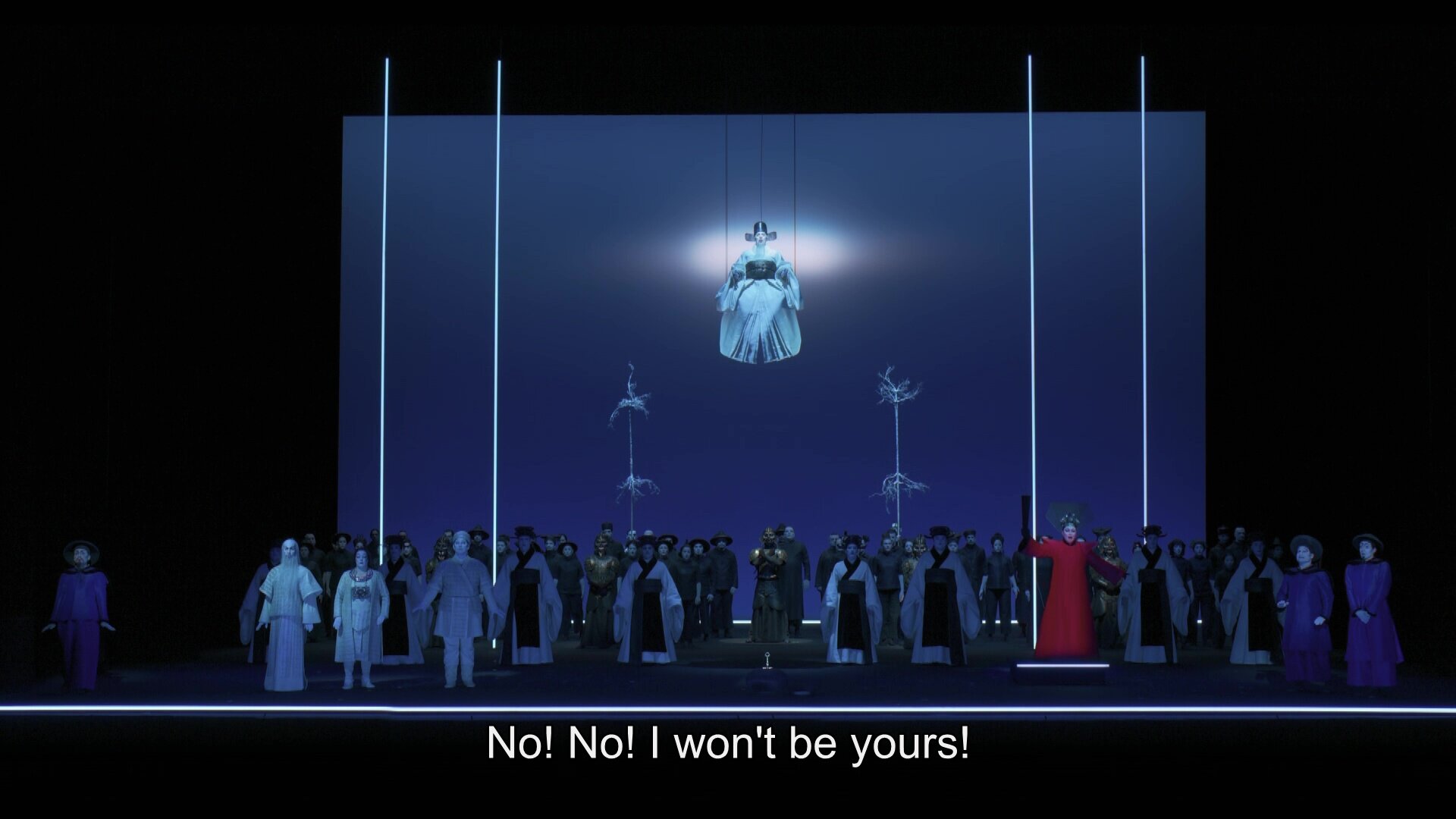

Another typical Wilson twist is to have Turandot appear high above the stage from a wing (when it time to send off the Prince of Persia to the chopping block):

Here’s a near shot of Gregory Kunde as Calif:

Ping, Pang, and Pong try to discourage Calif from playing the deadly riddle game. Most of the singers are quite static, almost like a concert version of the opera. But Wilson makes the 3 jesters into roving accent characters in constant Brownian motion accentuating the stability and gravitas of the lead singers:

And here’s another aerial pose, this time by Calif after he challenges Turandot to play the royal riddle game. After leaving the stage he picks up part of Turandot’s costume and her big black fan:

Every chorus member seems to have a unique presentation:

The Son of Heaven or Imperatore Altoum (Raúl Giménez) descends from the fly and hangs at least 20 feet above the stage. The center of the five cables is his safety line:

Turandot starts the deadly game:

Wilson uses video when necessary. The artwork on the back wall below appears while the riddle game is played and suggests a brier patch or the neurons in the brain. Note the vertical light bars that direct your attention to the the star singers:

Wilson likes to use trees, or dried remnants of trees. Here the trees serve as royal staffs. The twist is that the staff bearers rotate the staffs from time to time simultaneously and this small motion instantly rivets your attention:

The abstract structure seen below is not a video image. It’s a huge box with perforations lowered from the fly, and you see here the front and the back of the box, all suggesting the complexity of the City of Peking:

From time to time Wilson wakes you up by shifting from a blue to a red background:

And my favorite twist from this production is the beam of light that crowns Turandot at the end. The beam slowly descends from the fly and appears to end on the center of the top of Turandot’s head. How did Wilson create this image live on the stage? I think it may be a perfectly straight but light-weight LED light bar that can be slowly guided from above to the target. Another unique experience for the star soprano:

Wilson is above all else an architect of light in his designs. Most other productions of Turandot use a lot of light to show off their fancy designs for the Emperor’s court. But Wilson is interested in the soul of things—not the exterior. So his stages tend to be rather dark, and I am distressed at how gloomy our screenshots look on a computer display. But on my TV, I have no trouble seeing quite will well and exactly as Wilson intended.

You probably know that Puccini died after he finished the score through the death of Liù. Music to end the opera has been composed by others. Wilson has his own mild twists to the ending, so just be alert. Liù dies standing up with a tilt of her head and one hand. Wilson is not a director to pander to prurient interests, so Calif, several yards away, throws Turandot her first kiss from a man. Do you think she will warm up later?

I can’t show you here perhaps the best thing about this recording: the sound track. Luisotti and the music forces of Teatro Real worked hard on preparing the music. All the singers equal or exceed the competition. Alas, there is not a word in the keepcase literature about the fine job done rehearsing, performing, miking, mixing, recording, and mastering the sound. According to Patrick Mack, who wrote a beautiful review of this title for parterre.com, the recording was originally made for French TV by sound engineer Javier S. Chameleon. I kept hearing nuances in the orchestra score I missed before even though this is the 7th HDVD I’ve reviewed of this opera. Mack points out you can hear an organ come in at the climax of Act II. So if you are a musician or someone with an elite sound system, this title might well be the best sound recording of Turandot ever.

Now to sum up with a grade. I like Wilson’s symbolic approach to directing and staging, which helps me focus on the music and singing. I think the video overall is rather dark. But the excellent sound makes up for this, and I wind up with an A. If you’re a fan of modern art, this might be an A+ for you. Even so, this would probably not be the first choice for a newbie to Turandot. I would still start out a beginner with the Met Zeffirelli glitter-orgy. Or for something really edgy, try the Stefano Poda disc.

Here’s a clip from a French media source:

OR