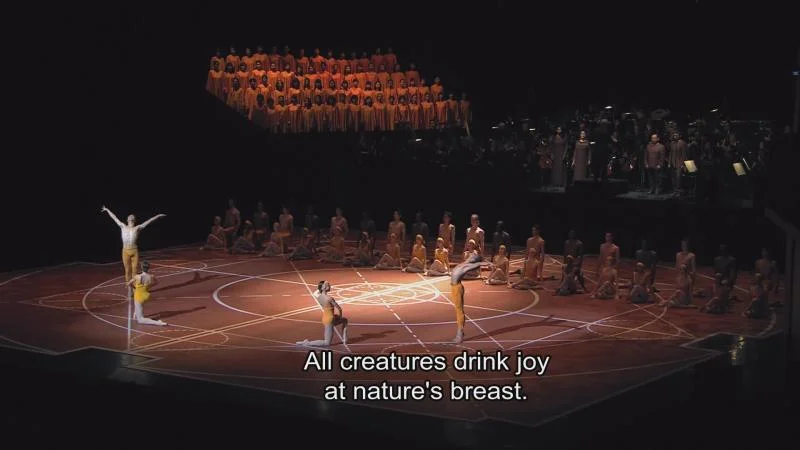

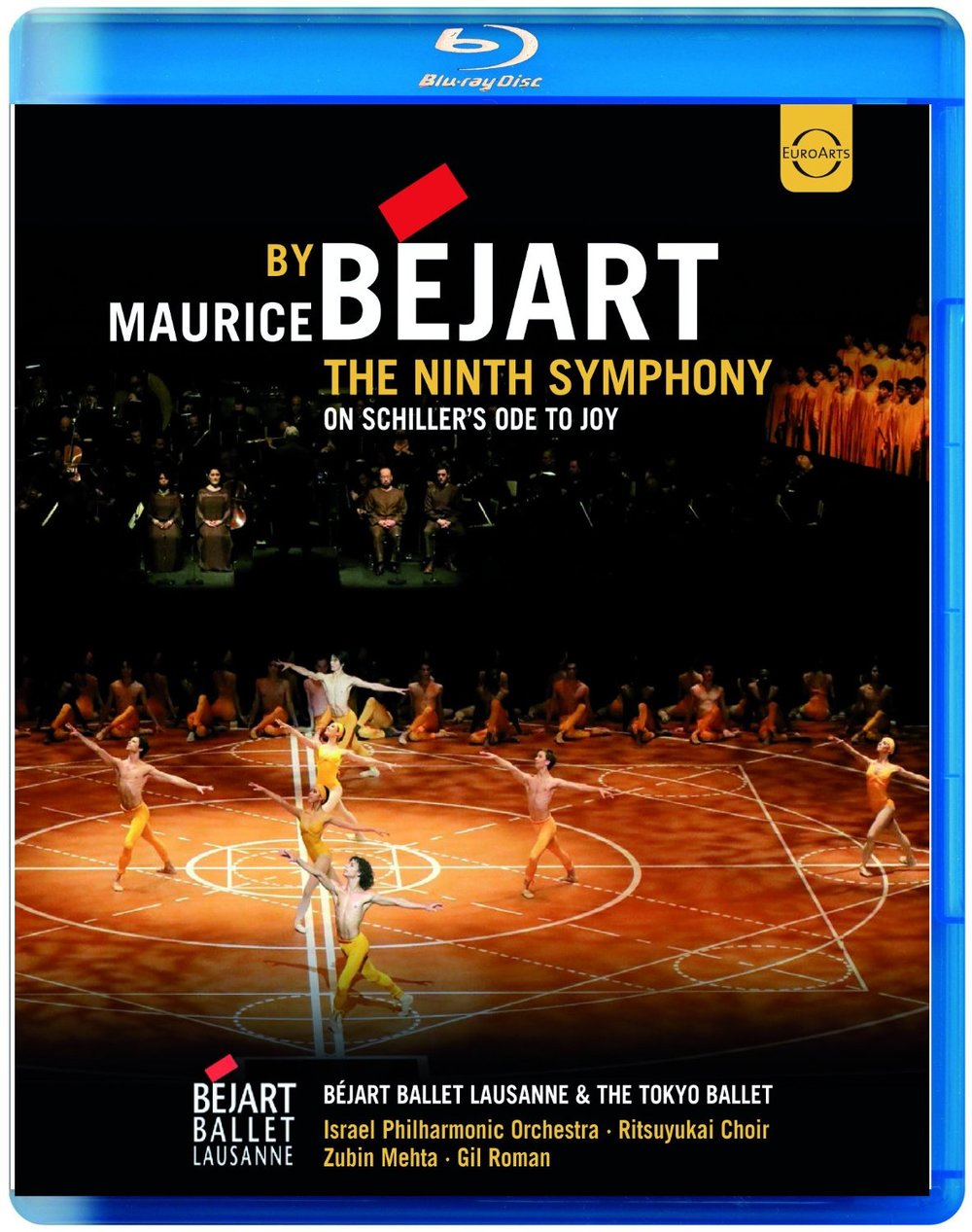

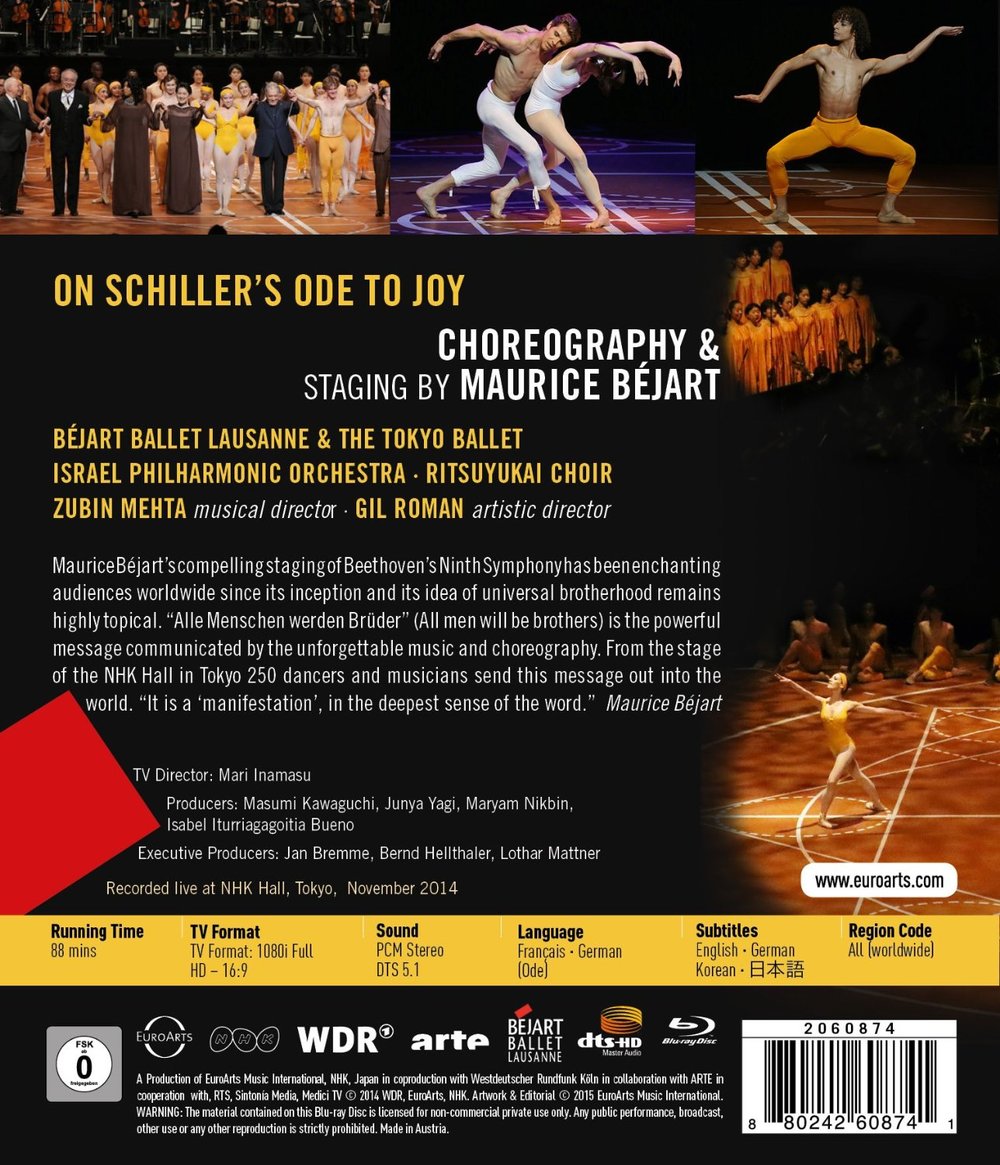

The Maurice Béjart The Ninth Symphony on Schiller's Ode to Joy modern dance was performed 2014 by the Béjart Ballet Lausanne and the Tokyo Ballet on the stage of the NHK Hall in Tokyo. Texts by Friedrich Nietzsche (Prologue) and Friedrich von Schiller (Ode to Joy). Music is Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Percussion by Thierry Hochstätter and jB Meier (Citypercussion). Choreography and staging by Maurice Béjart (1927-2007) remade by Béjart Ballet Lausanne Artistic Director Gil Roman with help of Piotr Nardelli. Soloist dancers are Dan Tsukamoto, Mizuka Ueno, Iori Nittono, Aya Takagi, Kathleen Thielhelm, Masayoshi Onuki, Elisabet Ros, Julien Favreau, Lisa Cano, Fabrice Gallarrague, Pauline Voisard, Felipe Rocha, Oscar Chacon, Keisuke Nasuno, Marsha Rodriguez, Cosima Munoz, Mari Ohashi, Kwinten Guilliams, Aldriana Vargas Lopez, Hector Navarro, and Alanna Archibald. Beethoven's Ninth Symphony is performed by the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and the Ritsuyukai Choir conducted by Zubin Mehta with Chorus Master Fukiami Kuriyama. Soloists for the Ninth Symphony are Kristin Lewis (soprano), Mihoko Fujimura (mezzo-soprano), Kei Fukui (tenor), and Alexander Vinogradov (bass). Prologue narration by Gil Roman accompanied by Citypercussion. Original sets and costumes designed by Joëlle Roustan and Roger Bernard; costumes realized by Henri Davila; lighting by Dominique Roman. Directed for TV by Mari Inamasu; Line Producer was Claudia Krüger; Producers were Masumi Kawaguchi, Junya Yagi, Maryam Nikbin, and Isabel Iturriagagoitia Bueno; Executive Producers were Jan Bremme, Bernd Hellthaler, and Lothar Mattner. Spoken language is French. The Ode to Joy is sung in German. Subtitles in English, German, Korean, and Japanese. Released 2015, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound output. Grade: A+

Béjart originally created his Ninth Symphony on Schiller's Ode to Joy in 1964. Béjart died in 2007, and he was succeeded by Gil Roman as head of Béjart's ballet company. The performance on this disc was a 50-year anniversary revival designed to be as expansive and "world-embracing" as feasible. So far it has been performed in Tokyo, Lausanne (Switzerland), and Monte Carlo to perhaps 40,000 people.

The huge collaboration required 3 years of work from 250 or so artists who were involved with ballet companies from Switzerland and Japan, an orchestra from Israel, a chorus from Japan, and dancing extras from Africa, plus opera singers from the United States, Japan, and Russia, jazz drummers from Switzerland and France, and a narration by the choreographer. Contributions also came, of course, from employees working in the companies providing the artists as well as squads of executives with multiple music broadcasting and recording companies. Wow! All of this to show a single ballet work performed to the music of a single symphony. Oops! I forgot to mention the unofficial European Anthem, the Ode to Joy by Schiller, which is baked into Beethoven's Ninth Symphony as well as 36 narrated lines of wild prose and poetry from everyone's favorite German garret-renting hermit and mad philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche---all marshaled to support us in our eternal search for . . . :

What you see above is the end of the Prologue. The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra rests in the shadows. Dancers from the Tokyo Ballet have taken their posts to listen to the Prologue, which is 100% straight quotes pieced together from three different works by Nietzsche. Nietzsche wrote in German. Roman, standing with the mike, recites the Nietzsche text in translated French, and the actual words of Nietzsche are given in German subtitles. The idea is that the ecstatic (Dionysian) joy of music and dance (illustrated by solos from the jazz drummers located on sub-stages) can elevate all men to a state of unity, after which they will no longer be interested in enslaving, raping, and killing each other. At the end of this review, I've attached the German text of the Prologue with the exact source in Nietzsche's writings for each line.

Béjart's choreography for Beethoven's 1st Movement ( . . un poco maestoso) is not very Dionysian. The music is formal and forceful (not free and fanciful). The dancers, all from the Tokyo Ballet, respond with moves and formations that seem defiant or even militaristic. You will immediately notice elaborate geometric patterns on the stage floor. The dancers use these guidelines constantly to keep lines straight and circles round. There is no suggestion in their steps that the Lord of Drunkenness is about. The most impressive thing is how accurately and uniformly the dancers work together, which you can see in the next 6 screenshots:

The level of skill and accuracy shown here is comparable to that of the classical ballet dancers in such big houses as the Paris Opera Ballet and the Bolshoi. I'm not used to seeing this kind of attention to detail in modern dance pieces with barefoot performers:

The Tokyo dancers worked very hard to attain the perfection you see here---their work is eerily beautiful:

The 2nd Movement (Molto vivace) is lighter and more relaxed than the opening. Now the dancers from Lausanne take over, but they have their own Japanese star, Masayoshi Onuki, to take the male lead:

Beethoven's 3rd Movement (Adagio molto e contabile) is relatively romantic. Here we get a splendid lovers' pas de deux between Ballet Lausanne stars Elizsabet Ros and Julian Favreau. The care and respect these partners show to each other is touching and inspiring. In the shadows other couples mimic each move perfectly and reinforce the lovers' serenity:

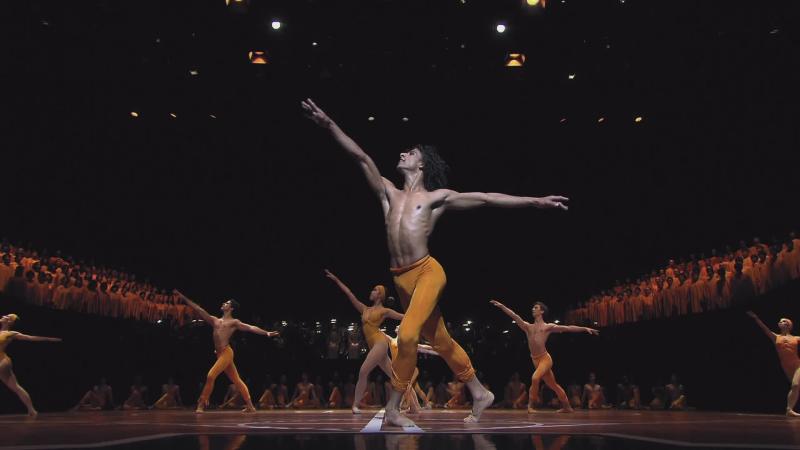

The 4th Movement (Presto--Allegro assai) is as long as some symphonies. It opens majestically and ends with Schiller's Ode to Joy. Below we see Ballet Lausanne star Oscar Chacon take the lead. He might have the darkest complexion of the Lausanne stars. Roman doubtless reserved him for this movement with its theme of brotherhood:

Below in the shadows are the singers at their curtain call. (The stage during the show was too dark for me to get decent images of the singers.) From your left to right is the African-American soprano Kristian Lewis from Alabama in the US; Mihoko Fujimura, a famous alto who was born in Japan but now possibly lives mostly in Europe; Kei Fukui, who is Japanese; and Alexander Vinogradov of Russia:

Below are African extras hired to make the cast more democratic:

And here is a fully-qualified "dancer of color" in a star role:

In the last scene, every available dancer is committed to form 4 concentric circles that move (in alternating directions) in a spectacular show of unity in diversity (sorry, no way to avoid all that motion blur):

If you want to make a good dance, you have to start with great music. Still, it took guts for Béjart to pick the Beethoven Ninth Symphony —what can you do in a dance to match Beethoven at his best? When I first put this disc in the player, I doubted that it could be done. Wrong again. Thanks to the remarkable discipline of massive forces dancing in the outer movements and the verve and sensitivity of the soloists throughout, the choreograph seems worthy of the exalted music.

You wouldn't buy this disc just for the music because you see very little of the symphony performance, but Mehta gets a good report out of the Israel Phil and the recording is fine. The singers are adequate, and Gil Roman's narration ties things together. Videographer Mari Inamasu was challenged with low light, but managed to turn out an attractive film. Because of the massive expense involved, this dance will probably not be shown often, if ever, in the future. We are lucky to have it so well-recorded in this excellent HDVD, which I'll grade "A+."

OR

Prologue to Béjart The Ninth Symphony on Schiller's Ode to Joy

Unter dem Zauber des Dionysischen schließt sich nicht nur der Bund zwischen Mensch und Mensch wieder zusammen: auch die entfremdete, feindliche oder unterjochte Natur feiert wieder ihr Versöhnungsfest mit ihrem verlorenen Sohne, dem Menschen. Freiwillig beut die Erde ihre Gaben, und friedfertig nahen die Raubthiere der Felsen und der Wüste. Mit Blumen und Kränzen ist der Wagen des Dionysus überschüttet: unter seinem Joche schreiten Panther und Tiger.

Freude!

Erhebt eure Herzen, meine Brüder! Hoch. Höher! Und vergesst mir auch die Beine nicht! Erhebt auch eure Beine.

Singend und tanzend äussert sich der Mensch als Mitglied einer höheren Gemeinsamkeit: er hat das Gehen und das Sprechen verlernt und ist auf dem Wege, tanzend in die Lüfte emporzufliegen. Aus seinen Gebärden spricht die Verzauberung. Und tönt auch aus ihm etwas Uebernatürliches: als Gott fühlt er sich, er selbst wandelt jetzt so verzückt und erhoben, wie er die Götter im Traume wandeln sah. Der Mensch is nicht mehr Künstler, er is Kunstwerk geworden.

Tanze nun auf tausend Rücken,

Wellen-Rücken, Wellen-Tücken –

Heil, wer neue Tänze schafft!

Tanzen wir in tausend Weisen.

"Frei" sei unsre Kunst geheißen,

"Fröhlich" unsre Wissenschaft!

Wer nicht tanzen kann mit Winden,

Wer sich wickeln muß mit Binden,

Angebunden, Krüppel-Greis,

Wer da gleicht den Heuchel-Hänsen,

Ehren-Tölpeln, Tugend-Gänsen,

Fort aus unsrem Paradeis!

Raffen wir von jeder Blume

Eine Blüte uns zum Ruhme

Und zwei Blätter noch zum Kranz!

Tanzen wir gleich Troubadouren

Zwischen Heiligen und Huren,

Zwischen Gott und Welt den Tanz!

Man verwandele das Beethoven'sche Jubellied der Freude in ein Gemälde und bleibe mit seiner Einbildungskraft nicht zurück, wenn die Millionen schauervoll in den Staub sinken: so kann man sich dem Dionysischen nähern.

Jetzt ist der Sclave freier Mann, jetzt zerbrechen alle die starren, feindseligen Abgrenzungen, die Not, Willkür oder »freche Mode« zwischen den Menschen festgesetzt haben.

Jetzt, bei dem Evangelium der Weltenharmonie, fühlt sich Jeder mit seinem Nächsten nicht nur vereinigt, versöhnt, verschmolzen, sondern eins, als ob der Schleier der Maja zerrissen wäre und nur noch in Fetzen vor dem geheimnissvollen Ur-Einen herumflattere.

Notes:

Most of the text (often quoted out-of-order) is prose from the last paragraph of Chapter 10 of Die Geburt der Tragödie. Underlined text is prose from the last paragraph of Vom höheren Menschen, #17 of the Fourth Part of Also Sprach Zarathustra. Poetry in bold is from An den Mistral, Ein Tanzlied.